Despite Housing Woes, Architectural 3D Printing Thrives

Last year, Mark Mackie spotted a trend that was eerily familiar to him. Architectural design and model making was entering the same phase that mechanical design and parts making had experienced a decade before: a transition from 2D to 3D design, and all the pains and promise that accompany it.

|

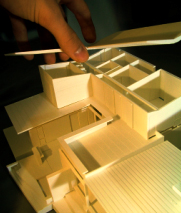

3D-Printed Mountain Lodge Model

Photo Courtesy Sweet Onion Creations |

Mackie and his Quickparts cofounders were a couple years late to the mechanical game - they didn't launch the rapid prototyping service provider until 1999. By then, the revolution was well under way. "I wish we had gotten into the mechanical marketplace in the beginning. We'd certainly be bigger than we are today," laments Mackie, executive VP of Quickparts and leader of QuickARC, its new architectural modeling division.

Determined to not miss-time this opportunity, Mackie launched QuickARC in October, 2007. Since then, despite the housing slump, the division is up to about 5 projects a week. "We had our best month ever in April," Mackie says.

QuickARC isn't exactly on the bleeding edge. Some architects and builders have been using additive manufacturing to create architectural models for a number of years now. It's just that better and cheaper rapid prototyping processes, combined with increasingly CAD-savvy architects, means that computer renderings are steadily being replaced by 3D-printed scale concept models. According to a number of service providers, the trend is so strong that it's overpowering the retrenchment in residential construction.

Technologies

QuickARC makes 65% of architectural models using the stereolithography (SLA) process. This is more a tribute to Quickparts' existing machine base than anything - the company has 47 SLA machines. QuickARC builds 30% of its models using six Z Corp. 3D printers, and the remaining 5% are built using selective laser sintering (SLS), fused deposition modeling (FDM), or polyjet. Mackie admits that it is cheaper to use a 3D printer, but that as the model increases in size, the cost advantage disappears, due to the effort required in piecing component parts together. Using 3D Systems' Viper Pro SLA System with a build capacity of 650 x 750 x 550 mm using a large size resin delivery module, "we can knock the piece out in one build," he says.

At RedEye ARC, RedEye On Demand's new architectural and home builder model maker, the technology of choice is FDM. Once again, this is due more to RedEye's origins than anything (RedEye is FDM system manufacturer Stratasys' service bureau arm and has 85 machines in Minnesota, 15 in Europe, and 5 in Australia), but there are some advantages. RedEye specializes in what it calls an "interactive model," where roofs and floors are removable to allow for a better view of hidden features. "Other technologies can't do that because of the supports required," says Jeff Hanson, manager of business strategy and development at RedEye ARC.

Hanson is making the comparison to 3D printing, which is the most widely used for architectural model making due to Z Corp.'s marketing to architects, and its superior speed and cost. The 3D printers use a white powder that is bonded by liquid adhesive that is deposited by an inkjet print head. The resultant model looks good, but is somewhat brittle.

Software

Of the service providers RapidToday spoke to, almost all said that extensive file repair was often necessary to get drawing files 3D printable. Mackie at QuickARC put it at 20% of total cost, or US$600 of a typical US$3,000 model build. (For perspective, he says this model will use only about US$250 of SLA resin, which sells for about US$1,000 a gallon.)

There are two problems will architectural CAD files. One is that most architecture software programs, like ArchiCAD and Revit, don't allow direct export to STL files, the RP standard. So, files have to be exported to DWG, imported into AutoCAD, then exported to STL. Direct to STL is likely to be offered with the next release of these professional programs, although it may be a while before programs like SketchUp offer this capability. (QuickARC has just started offering a SketchUp to .stl converter.)

Less easily fixed are the gaps and holes in architectural CAD files that may not be easily visible, but will short circuit a rapid prototype. These problems are now painstakingly found and fixed by specialists at rapid prototyping service providers, using mesh repair programs like Magics, VisCamRP, MeshWorks, and 3Data Expert from DeskArtes.

A quick software solution to this problem is not imminent, so 3D model makers are encouraging architects to develop standards that guarantee that CAD files are inherently sound. "It's no different than how mechanical engineers had to learn about draft angles and moldflow for plastic injection modeling. From an industrial design standpoint, the same thing needs to happen in architecture," says Charles Overy, founder and director of Colorado model shop LGM.

|

Stereolithography Model with Removable Roof Photo Courtesy QuickARC |

Of course, as 3D printing costs decrease, amateur architects and casual homeowners (who want a scale model of their house) will start to get into the game. Service providers will ignore the power of SketchUp at their peril. The free (a Pro license costs $495) Google program has reportedly become wildly popular due to its easy-to-learn interface and simple "push/pull" approach to drafting.

"The adoption rate for SketchUp is just astounding," reports Jake Cook, cofounder of Sweet Onion Creations, a 5-person Montana architecture modeler. A user can make his own models, or download existing models from Google 3D Warehouse. Sweet Onion has downloaded and built a good portion of downtown Jacksonville, FL for a customer, as well as the Chrysler Building, Guggenheim Museum, and Disney Concert Hall. "They are pretty messy when they come out," Cook says. He figures he spent about four hours getting the three landmark buildings patched and ready for Sweet Onion's Z Corporation printer. In June, Cook is delivering a talk on 3D printing from SketchUp files at Google's 3D Basecamp.

Resilience

As homebuilders and residential developers have retreated from sales model making, other customers have filled the gap. "When I started four years ago, I thought my main business would be architects," says Brian Ehler, founder and owner of California-based 3D Reprographics. He was wrong - only about 10% of his business originated there. Now, it's 80% of his work. "It's been a big change," he says.

(An even bigger change: Ehler is merging 3D Reprographics with Washington, D.C.-based ABC Imaging, a printing and document management company with branches across the U.S. and plans for international expansion. ABC already has a handful of Z Corp. printers, but didn't have a dedicated team to run them. Ehler's company will become a division of ABC. The merger is scheduled for later this month.)

Launched just this February, RedEye ARC targeted the home building industry, but was surprised by the level of interest from the industrial sector. RedEye's Hanson says industrial customers will laser scan their existing interiors, and use the point cloud data to create facility layouts, then insert the proposed addition. They will seek a 3D model for convincing the top brass, or for permit generation, or for communicating with subcontractors, he says.

The Future

Despite the parallels with mechanical design, the architecture/engineering/construction (AEC) industry will forge a unique path. For one thing, architects aren't as technology savvy as mechanical engineers - their work is as much art as it is science. For another, architects are more likely to work independently. According to the Boston Society of Architects, 80% of firms in the U.S. are composed of six or fewer architects. For every Kohn Pederson Fox Associates, which has two 3D printers in New York and one in London, there are scores of small firms that are happy to outsource the model making function.

And companies like LGM are happy to oblige. LGM bought a Z Corp. 402 printer eight years ago, making them one of the first model shops in the three dimensional printing business. Today they have three Z printers, but still use CNC milling for sizable terrain forms, and laser-cut hand-built techniques where appropriate (the bigger, the more cost effective).

LGM Director Overy questions the architectural modeling experience of newcomers like QuickARC and RedEye ARC, but chances are there will be enough business to go around. "We wouldn't have gotten into the business if we didn't think it would go big," says RedEye's Hanson.

See our new list of 10 Best RP Architectural Scale Model Service Providers

Want to comment on this article? Visit our 3D printing forum.

Want to read more? Visit our 3D printing archive.